The right to keep and bear fireworks

The political arena is hotter than ever with fights raging over rights and freedoms and all that good American stuff. But one topic missing from these debates only gets the attention it deserves for about a week every year each July: the right to keep and bear fireworks. It's a right heavily restricted in sixteen states and straight-up illegal in Massachusetts. Yes, Massachusetts, home of the Boston Tea Party, that act of defiance that sparked our patriotic tradition of blowing things up.

In the Pennsylvania Wilds — the romantic name a tourism agency gave to the hick region of the state where I reside — things go boom year-round. It could be someone detonating explosives to open up a strip mine, a truck backfiring, a firearm normal-firing, or someone celebrating making bail with a bottle rocket. But during Independence Day week — heck, it lasts all summer long — the whizzing, whistling, whirring, bang, pop, kaboom! sounds come on in full-force as the natives do their best to remind the Redcoats not to get any ideas…

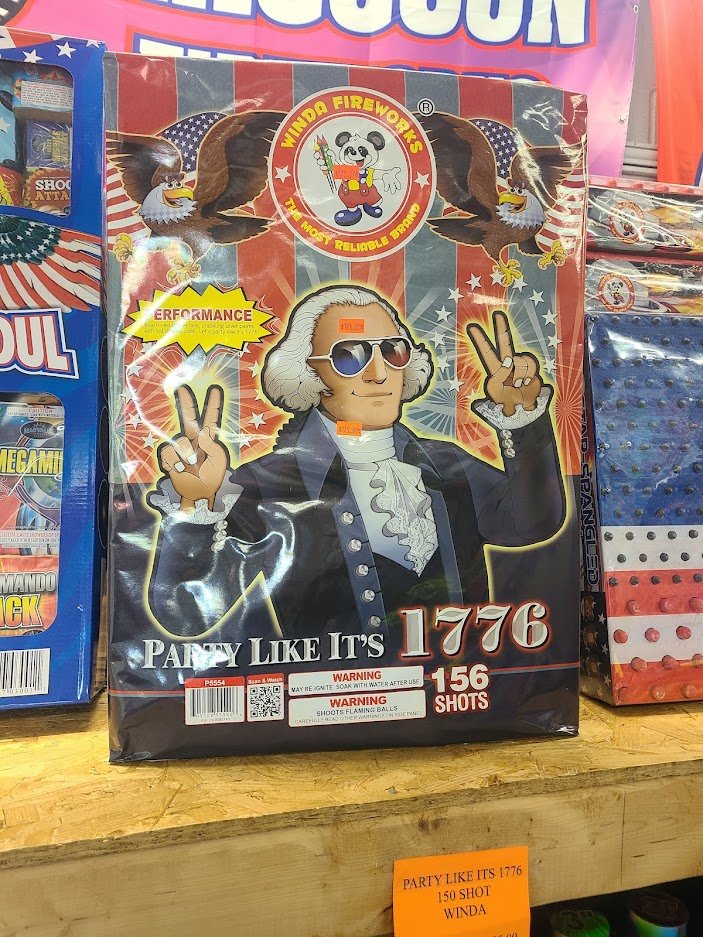

Fireworks are as American as apple pie and not kissing people when you greet them. A merchant at one of my local fireworks emporiums (we have three) explains, “A guy was in here the other day and said his neighbor called the cops on him for setting off fireworks and the dispatcher was like…so?”

“What do people like about fireworks so much?” I ask the vendor, who, by the way, sleeps on a tiny cot inside his fireworks tent for ten consecutive nights in July to safeguard his wares.

“I think it’s a little bit of danger, the lights, the spectacle,” he says. “It draws a crowd — especially if you’re the one setting them off. It’s like, look what I did. It’s a big party.”

There are, of course, more practical uses for fireworks.

“Some guy said he had to get rid of a groundhog under his house so he bought a bunch of these,” the storekeeper says, running his hand over a pile of “Mammoth Smoke” sticks, which I’m told “just make a bunch of smoke.”

“Yeah, some other guy came in and said he was going to shoot a music video under a bridge and bought like ten of them,” another salesman chimes in.

I visit another fireworks store the next county over. It’s a brick-and-mortar place that’s open half the year, with special hours leading up to New Year’s Eve. When I show up on June 30, it’s busier than our local grocery store the day before Thanksgiving.

“Wow, it’s really crowded in here, huh?” I say to the proprietor, who is open-carrying a Glock on his hip.

He shrugs.

“This isn’t bad,” he says. “In 2020, during Covid, we had people snaking through the parking lot, lined clear down the highway. We had to limit the number of people we could let in the store at one time, or no one could move.”

“What are some of your most popular items?”

“Roman candles and the bigger, 500-gram cakes.”

The man’s voice drifts off as he just repeats the word: “Bigger, bigger…”

“It really depends on personal preference,” his sister says. “There’s everything for everybody.”

I survey the scene: there’s a sweet-looking woman with her hair in a bun who is probably picking up sparklers for her grandkids. There’s a father loading a shopping cart with his two teenage sons. My mental note-taking is disrupted as I must slide out of the way of a dignified-looking gentleman in a suit and tie carrying a giant box of fireworks.

“What do you like about fireworks?” I ask a few folks. They stare at me a second and sort of frown, as if to say, “What do you mean, ‘Why do I like fireworks? That’s like asking, ‘Why do you like fair weather and free pizza?’”

This article was originally published by The Spectator. Read the full piece here.